Scientists have discovered several ancient shark skulls and an almost complete skeleton in Morocco’s eastern Anti-Atlas Mountains.

The remains belong to two species of the genus Phoebodus—a primitive group of now-extinct species which researchers previously only knew about due to the discovery of isolated teeth and fin spines, according to a study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

While ancient shark teeth are commonly found around the world, the latest find is surprising because shark skeletons are made of cartilage—a rubbery tissue that doesn’t preserve as well as bone.

As a result, there is a significant gap in the early shark fossil record—which is mostly based on isolate teeth and scales.

A team of researchers led by Christian Klug from the University of Zurich in Switzerland uncovered the shark remains in a layer of sediment dated to between 360 and 370 million years ago, National Geographic reported.

This area was once the site of a shallow sea basin, and the particular conditions that existed there—notably low oxygen levels and limited water circulation—meant that, surprisingly, parts of the shark skeletons were preserved.

The condition of the remains had deteriorated due to the effects of time, however, the team conducted CT scans on some of the skeleton parts revealing intriguing details about these ancient sharks.

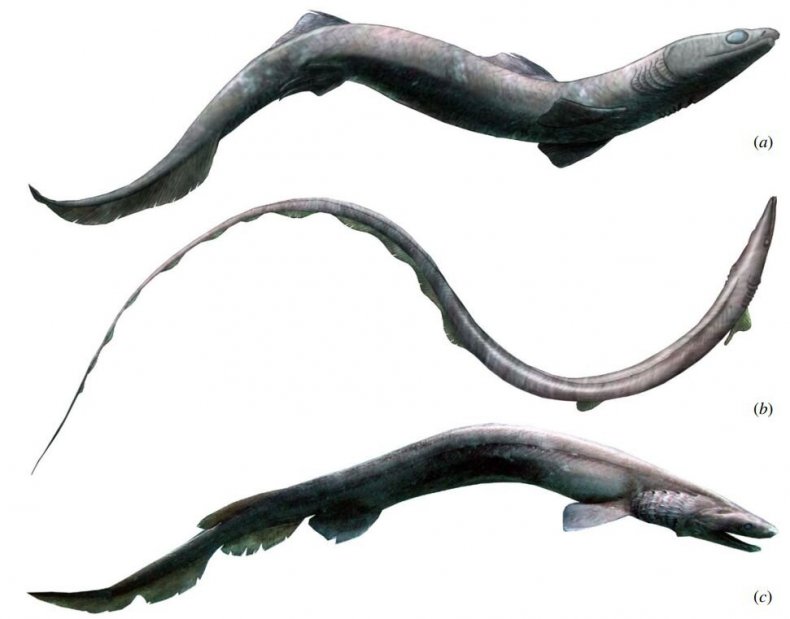

The team’s scans indicated that the Phoebodus sharks had long snouts and eel-like bodies, making them remarkably similar to the frilled shark—a strange, primitive animal which can be found today in the deep-sea and open ocean.

The frilled shark features a long cylindrical body which can measure up to 7 feet in length. The rare shark—which is “near-threatened” with extinction—is named for the frilly appearance of its gill slits, according to non-profit Oceana.

The similarities between the body shape and teeth of Phoebodus and modern frilled sharks suggests that they might have fed in similar ways—i.e. catching prey and swallowing it whole—despite being only distantly related, according to the researchers.

“The frilled shark is a specialized predator, with the ability to suddenly burst forward to catch its prey,” David Ebert, from the Pacific Shark Research Center, told National Geographic. “The inward-pointing teeth then help to make sure the prey can only go one way: into its throat. Maybe Phoebodus did something similar.”

Even though the frilled shark is rarely encountered by humans, Ebert says it is unlikely that there may be members of the ancient Phoebodus genus still alive today, hidden in the world’s oceans.